The Gingerbread House Literary Magazine Editors decided it might be fun to ask some of our favorite authors a question:

Do you find you have a particular myth, fairy tale, or other text, that you return to again and again, that serves as a sort of ur-text/blueprint for your own craft? How has this shaped you as an artist?

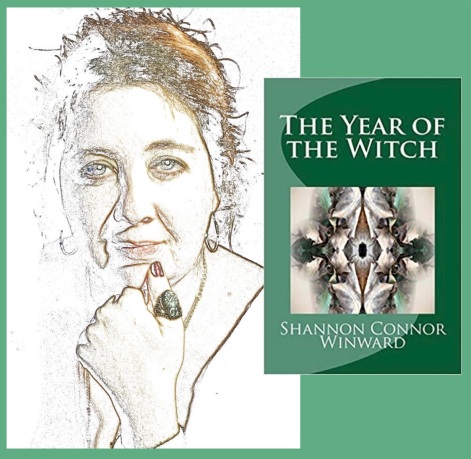

LINDSAY MERBAUM

In June 2015, GBH published Lindsay Merbaum’s “The Minotaur’s Mother.” Now we’re happy to let you know Lindsay will release her debut queer feminist horror novel, THE GOLD PERSIMMON in October. Merbaum received her MFA in Fiction from Brooklyn College. In addition to Gingerbread House, her short fiction has appeared in PANK, Anomalous Press, The Collagist, Day One, Epiphany, Gargoyle, Harpur Palate, Hobart,and Whiskey Paper, among others. Essays, reviews, and interviews can be found in Electric Literature, Bustle, Bitch Media, The Rumpus, and more. She is also an editor of book reviews at Necessary Fiction.

AS A BONUS, all pre-orders come with a cocktail compendium, featuring The Gold Persimmon cocktail and others. Visit Creature Publishing today to order your copy: https://creaturehorror.com/books/the-gold-persimmon.

I started reading Greek mythology at a very young age, probably too young for myths about rape and jealousy. Yet they were some of the first narratives to ever capture—and shape—my imagination. I was particularly enraptured by the story of Persephone.

The thing that obsesses me about Persephone is her story is not her own. While gathering flowers in a field with her handmaids, she wanders towards a strange, irresistible bloom. Once she reaches it, the ground opens up beneath her and Hades, god of the underworld, steals her away and makes her his bride. But once this abduction—often called “the rape of Persephone”—is done, Persephone mostly disappears from the myth, her suffering rendered invisible to the reader. Instead, the focus shifts to her mother, Demeter/Ceres, goddess of agriculture, who wanders the Earth seeking her daughter. It’s Demeter’s grief that causes the crops to fail. The earth turns dark and fallow. Along the way, Demeter also disguises herself and visits some humans. A mother finds the goddess placing her babe in the hearth and cries out. Demeter’s intent was to gift the child with immortality, but she revokes that offering as a rebuke against the mother. (Really, what was she supposed to do? Allow a stranger to burn her baby?) As a maternal figure, Demeter is devoted to her offspring. As a goddess of the life-sustaining harvest, she is shockingly indifferent to the plight of the humans who depend upon her.

In the end, Zeus (king of the gods and Persephone’s own father, who secretly gave Hades permission to take her as his bride) intervenes, or else all the humans will die and leave the gods with no one to worship them or make offerings. Hades is forced to give Persephone up, but it’s too late: she’s already eaten some pomegranate seeds, the food of the dead. Seeds represent life and growth, and what more do the dead long for than to live again? So a deal is brokered. Hades and Demeter will split custody, each spending half the year with Persephone. When she’s with her mother, the world is green and abundant. When she’s at her husband’s side, it’s dark and lifeless. This is the explanation for the changing of the seasons. An earlier version of this life/death cycle can be found in Sumerian mythology, only it’s Dumuzi/Tammuz, consort of the goddess Inanna, who must dwell in the underworld. In some versions, his loyal sister willingly takes his place for part of the year. Women’s ritual mourning of Tammuz is disdainfully referenced in the Hebrew bible as a pagan practice.

How Persephone feels about this arrangement is never discussed. What she suffers in the underworld remains a mystery, as if her experience is beside the point. And yet, if she had a voice to speak, what could she tell us about this liminal state of being, caught between the worlds of the living and the dead? As a queer woman writer, I’ve become fascinated by filling in those gaps. I am obsessed with in-between spaces, which is why my novel is set within two surreal hotels. Hotels are public spaces, full of strangers in close quarters, where private narratives unfold behind closed doors. I wanted to see within those portals.

The myth of Persephone is about a hurt girl. She’s a bargaining chip, lacking agency or outward character development. She’s just a pawn in the story of far more powerful figures: men, deities. I wanted to give voice to underdogs, to explore their grief without turning it into a precious thing. In other words, to plumb the depths of their pain without losing the texture of their humanity. It follows then that Jaime, my lynchpin narrator, is female-bodied and nonbinary. They occupy an in between space and suffer from our culture’s collective discomfort with boundary crossing and binary rule-bending. But they are, by definition, not a damsel, no wanton object of desire. Their allies who protect them, and whom they protect in turn, are cis women.

My debut novel is full of secrets and stories within stories. Instead of an underworld, I created strangely beautiful and unsettling hotels where people go to mourn their private pain, where guests arrive but an inexplicable disaster beyond the scope of their understanding occurs and they cannot leave. I lifted the curtain, opened the door, and descended into the darkness.

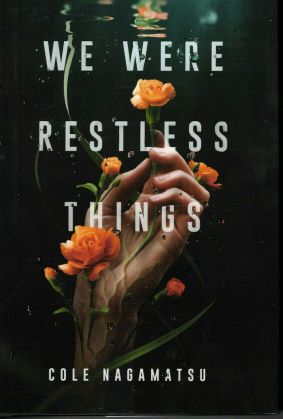

COLE NAGAMATSU

COLE NAGAMATSU writes fiction. Her short stories have been featured in West Branch, Tin House, cream city review, Bartleby Snopes, PodCastle, and other print and online publications. She is the editor-in-chief of Psychopomp Magazine, a journal of genre-bending prose, and she works as a visiting assistant professor of creative writing at St. Olaf College. Cole resides in Minnesota with her partner and their cat, Kalahira. Her first novel, We Were Restless Things, was published by Sourcebooks Fire.

I don’t think there’s one specific fairy tale I return to as a blueprint for my writing in general. In the case of certain specific projects of mine, however, I’ve tried to adapt “The Sea-Hare” a couple times in different genres, but it proved to be a difficult one. My debut YA novel, We Were Restless Things, was loosely inspired by northern European tales about shapeshifting freshwater spirits like nix or nokken that lured people to drowning. I write a lot about shapeshifting generally. Right now I’m at work on a retelling of “East of the Sun, West of the Moon,” also a shapeshifting story. So while I don’t necessarily have one myth or tale that influences me routinely in terms of structure and theme, many fairy tales that evoke shapeshifting—whether in the form of people shifting into animals or non-human beings appearing human on the surface—probably permeate my work in unconscious ways. I write often about nature, death, and identity, and I can see ways that shapeshifting myths would connect to all those themes.

You can find We Were Restless Things at Amazon and other major booksellers.

SEQUOIA NAGAMATSU

SEQUOIA NAGAMATSU is the author of the forthcoming novels, HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK and GIRL ZERO (William Morrow/Harper Collins and Bloomsbury UK) and the story collection, WHERE WE GO WHEN ALL WE WERE IS GONE (Black Lawrence Press), silver medal winner of the 2016 Foreword Reviews Indies Book of the Year Award, an Entropy Magazine Best Book of 2016, and a notable book at Buzzfeed. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in publications such as Conjunctions, The Southern Review, ZYZZYVA, Tin House, Iowa Review, Lightspeed Magazine, and One World: A Global Anthology of Short Stories, and has been listed as notable in Best American Non-Required Reading and the Best Horror of the Year. Originally from Hawaii and the San Francisco Bay Area, he was educated at Grinnell College (BA Anthropology) and Southern Illinois University (MFA Creative Writing). He co-edits Psychopomp Magazine, an online quarterly dedicated to innovative prose, and teaches at St. Olaf College (and has previously taught at the College of Idaho and the Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing). He lives in the Twin Cities region of Minnesota with his wife, the writer Cole Nagamatsu, and their cat Kalahira. @SequoiaN/SequoiaNagamatsu.com

If I’m honest, I picked up Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics based solely on the title when I was nineteen. I liked space and metaphysical things, so it seemed like a no brainer. I’ve always been a lover of tales and myths, the origin stories of how we and the world came to be. But Calvino’s work (and later Marquez, Borges, Carter, and Bernheimer) introduced me to the ongoing tradition of the tale—stories that burned with magic and wonder but sometimes veer away from the flatness and dependency on archetypes and recognizable social mores that often defines the fairy tale or myth. The stories in Cosmicomics dance with the surreal and absurd and the spaces where science cannot help but become spiritual. In this book, we have the heart of the tale or myth, but a science-fictional heart that looks into the origins and early days of the universe and our planet before recorded history.

The first story, “The Distance of the Moon,” plays with the fact that the moon was once much closer to the Earth billions of years ago. In our reality, the moon once orbited Earth at a distance of approx. 20,000 miles as opposed to its current distance of 238,000 miles. But in the world of Calvino, you could prop a ladder up to the moon and somersault onto the lunar surface that looked like fish scales. Once there, you could harvest moon milk, thick like cottage cheese, beneath the scales. Of course, the characters in the story with unpronounceable names like Qfwfq and Captain Vhd Vhd, which adds to the sense that this tale occurred in a very different time/reality do not know the moon is slowly moving farther away. This lunar movement is the backdrop of a love triangle and the eventual separation of lovers. When I first read the story, I was of course struck by the blending of science, origin story, and love story, but I think what I took from “The Distance of the Moon” was the sense of wonder that would lead someone to reach out to the moon coupled with the loneliness and exile of someone who might be reaching back to the Earth. In other words, the tone and themes at play amidst the magic—the emotion caught in the spaces between the Earth and Moon.

It’s not a huge surprise then that I think of “The Distance of the Moon” as an influence seeing that I’m a writer whose fabulism often entertains familial estrangement, death/grief, and conceptions of memory. My characters may not be reaching for the moon, but they are often reaching for or surrounded by the strange, miraculous, and otherworldly. It is through navigating these spaces that my readers might understand the ineffable texture of the pain of my characters. It is on spaceships and in endless voids that my characters might heal and find each other.

If you haven’t read Calvino’s “The Distance of the Moon,” you can find a reading of it here: https://tinyurl.com/y2pq33un

SHANNON CONNOR WINWARD

Shannon Connor Winward is an American editor and writer of manifold things. Her work appears widely in places like Fantasy & Science Fiction Magazine, Analog, Gingerbread House, Enchanted Conversation, Eternal Haunted Summer, and Literary Mama. Shannon is an erstwhile recipient of many honors and awards including an emerging artist fellowship from the Delaware Division of the Arts. Her debut poetry collection, Undoing Winter (Finishing Line Press, 2014) won an Elgin Award for best speculative chapbook. Her first full-length book, The Year of the Witch (Sycorax Press), was published in 2018. In between parenting, writing and other madness, Shannon is slowly emerging from medically-induced hibernation. She hopes to resuscitate her literary journal Riddled with Arrows, later this year.

There’s one story I never tire of—one that I return to again and again—but it’s a story with many faces.

As a child, my favorite fairy tale was The Seven Ravens. At heart, I was the sad little girl with doomed older brothers; and I was the witch, hiding in my woodland castle, nursing grievances against the world. I thought cutting off a finger to make a key was hardcore—the coolest thing I’d ever read in a book. That story, as much as anything, set me on the path to genre writing.

The Seven is also one of those rare proto-feminist fairy tales that deserves a special place in our archives. I loved that it was the little sister of the story that does the saving. I wondered if I would have that kind of courage, if it came to it.

The myths that have fascinated me most as an adult are variations on a similar theme: Inanna-Ishtar, Orpheus. Demeter’s determined motherhood. The Spirit Wife—a Zuni myth about a bride lost twice to death when her mate can’t help but touch her a hair too soon. Across time and cultures, our storytellers have waxed poetic about the audacious strength of the human heart—strong enough, maybe, to wrest loved ones from the dark. Not every story works out as well as in The Seven—not every hero saves the day—but they all remind us that love is what binds us. For love, we could stand up to death and gods and stupid chance.

In my own life, one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do was love myself that much. As a young person I struggled with sickness and a cyclical kind of depression that would come over me regularly, like Persephone’s winter. I would go down, and down, and down again. If things had gone differently, I might never have made it back. But after a deep-dive into my own dark places, I eventually found the strength that I’d been searching for. The little sister saved herself.

I’ve since come to realize that so much of what I write reflects the katabasis story, the underworld journey of our myths and fairy tales. Sometimes I deal with it literally, in myth-punk poems and stories. Sometimes it’s an over-arching theme. My first collection, Undoing Winter, does both—the titular poem is a mash-up of the Demeter/Orpheus/Ishtar myths, while the overall arrangement of poems echoes the down-and-back again of a depressive cycle.

One could argue that The Year of the Witch, my first full-length book, does something similar with its seasonal wheel motif. What is a year, if not a journey into and out of darkness—of winter, or the natural tides of a lifetime? And yet, no matter how many times we make that journey, we find that the treasure in the deep-down usually has something to do with love. That is the stuff that drives me most, and draws me in. That is, to me, the ultimate story.

DAYNA PATTERSON

We’ve been so fortunate at GBH to have worked with Dayna since our very first issue! A frequent contributor, Dayna Patterson is the author of Titania in Yellow (Porkbelly Press, 2019) and If Mother Braids a Waterfall (Signature Books, 2020). Her creative work has appeared recently in POETRY, Ruminate, Sugar House Review, Thrush, and Tupelo Quarterly. She is a co-winner of the 2019 #DignityNotDetention Poetry Prize, and she has been a Sustainable Arts Fellow at Mineral School Artists Residency. She is the founding editor-in-chief of Psaltery & Lyre and a co-editor of Dove Song: Heavenly Mother in Mormon Poetry. daynapatterson.com

When I was very young, my mother wrestled with her own “blue beasts,” a debilitating depression that took her out of my life for almost a decade. We have a wonderful relationship now, but I think because of this early trauma, I will always be drawn to stories of parent-child separation and reunion. Hansel and Gretel abandoned in the dark forest. Rapunzel. Cinderella. (Isn’t the fairy godmother really a symbolic resurrection of the dead mother?) Dumbo is a childhood favorite.

My love affair with Shakespeare didn’t begin until I was a mother myself. When I encountered The Winter’s Tale, it electrified me. Perdita, the “lost” child, is abandoned in a desert in Bohemia where she is adopted by a good-hearted shepherd. I don’t want to give away the ending, but if you haven’t seen it, I highly recommend attending a performance. (And if you can’t see it live, Antony Sher plays a splendid tyrant.) Perdita is raised without a mother, as, indeed, so many characters in Shakespeare are. The daughters of Lear. Ophelia. Jessica. Miranda. They are all raised by fathers, as I was. Sometimes the lost child rejoins the mother, but most often not.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the crux of the argument between Titania and Oberon is a child that Titania has adopted and that Oberon wants for himself. (Okay, the child might be a mere token in an argument that actually centers on infidelity, but that’s beside the point.) In Shakespeare’s version, after Oberon takes the boy while Titania is love-drunk, there is no more mention of where the child ends up. That rankles me. What happens to him? Why does Titania, the adopted mom, seem to lose interest, even after the spell is broken? In my chapbook Titania in Yellow, I lean into my desire for mother-child reunion by riffing on and reshaping the story as Shakespeare left it. I imagine Titania hungry to be a mother, and I dig into the trickery used to con the boy from her. I imagine a fairy queen’s rage when she snaps out of the spell and realizes the child is gone.

Last summer, in a local performance, I watched as Titania and Oberon wrapped up the play by sharing the child, their underlying enmity extinguished. They passed a bundled babe back and forth lovingly as they blessed the newly united couples. Even though the child disappears from Shakespeare’s text and there’s no mention of reunion, I adore this innovative approach to the ending. It’s an ending I’ll continue to explore, to chase after in my own work.

ALYSSA QUINN

Featured in this month’s issue, Alyssa Quinn is the author of the chapbook Dante’s Cartography (The Cupboard Pamphlet, 2019). She is earning her creative writing PhD at the University of Utah, where she is a prose editor for Quarterly West. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Ninth Letter, The Pinch, Indiana Review, Hobart, Juked, and elsewhere. You can find her at alyssaquinn.net.

It would have to be the Tower of Babel. Babel is the archetypal story about misunderstanding and the failure of language, which are core concerns of my work. The thing against which I’m writing is almost always loneliness and solipsism—the fear that we are trapped irrevocably inside our skulls, and that true intimacy, true communion, is impossible. As Nabokov writes, “one of the main characteristics of life is discreteness. Unless a film of flesh envelops us, we die. Man exists only insofar as he is separated from his surroundings. The cranium is a space-traveler’s helmet. Stay inside or you perish.” Language is this magic thing that aspires to bridge the gap between craniums. Often it fails. Sometimes, miraculously, it succeeds. It’s these against-all-odds moments of real connection I’m reaching for when I write. As such, my stories frequently explore the tension between what is said, what is meant, what unsaid, what unsayable. They explore miscommunication, inadequate narratives, and failures of translation. At times, especially in my chapbook, the stories feature characters who obsess anxiously over the limits of language. These anxieties drive them to insanity or even death. But sometimes, my characters and I remind ourselves to breathe. Together, we remember that, yes, Babel may be the place where language falls short. But perhaps it is also the place language learns to play. Translation takes place at a slant. It is always a little off. Always contains gaps. As I translate what’s in my head onto the page, and as readers translate what’s on the page into their heads, my wish is that we may all continue to celebrate these gappy, slanty, magic ways that language does its work.

ANDREW MCSORLEY

Andrew McSorley is the author of What Spirits Return (Kelsay Books, 2019). He is a graduate of the MFA program in creative writing at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. His poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in journals such as The Minnesota Review, Blue Earth Review, Gamut Magazine, Gingerbread House Literary Magazine, SOFTBLOW, Rougarou, After the Pause, and the Lindenwood Review. He lives in Appleton, Wisconsin where he works as a librarian in the Seeley G. Mudd Library at Lawrence University.

There’s really nothing in the world to me like Greek mythology, and if there’s anything even approaching an ur-text for me, it would have to be The Odyssey. When I was very young my father sat down with me and we watched Jason and the Argonauts on television. Strangely, this was my first entrance into the world of Greek mythology. The stop-motion animation seems campy by today’s standards, but I was enthralled in this world I was seeing at the time. I wanted to learn more, and came, eventually down the line, to things like The Iliad and The Odyssey. I don’t think I’ve remotely attempted anything like The Odyssey (God help me), but it’s the perfect harmony of desire, chaos, and purpose-seeking that makes me come back to it over and over. While it’s never served as a literal “blueprint” for me, I think it serves as a creative marketplace, a text to go back to and purchase rhythms or images to use in a different recipe.

I’ve always wanted the worlds I create to contain monsters like the ones Odysseus encounters on his journey. They’re all so purposeful, sometimes well-mannered, and generally intelligent. In most cases, there’s nothing monstrous about them at all aside from their intentions or appearance. It’s hard to do something like this in poetry, to create something menacing that also blends in so well. I think that’s part of why, in crafting narrative poems, I tend to look inward so often. Since it’s hard to create those types of monsters out of thin air, it’s much easier to see them within ourselves, to see what common demons we are wrestling with at the time.

The Odyssey is the type of literature that made we want to start writing in the first place. It’s a language of pure invention and sets us down in every corner of the mind. Wherever Odysseus lands we find another struggle, but also another metaphor for surviving in the world. This is, at its heart, what poetry wants to do. At the very least, it’s what I want to do, and I think I have The Odyssey to thank for that.

SARAH ANN WINN

Sarah Ann Winn’s first book, Alma Almanac (Barrow Street, 2017), was selected by Elaine Equi as winner of the Barrow Street Book Prize. She’s the author of five chapbooks, the most recent of which is Ever After the End Matter (Porkbelly, 2019). Her work has appeared in Five Points, Kenyon Review Online, Massachusetts Review, Smartish Paceand Tupelo Quarterly, among others. She teaches writing workshops in Northern Virginia and the DC Metro area, and online at the Loft Literary Center. Visit her at http://bluebirdwords.comor follow her @blueaisling.

When I was seven or eight my grandmother bought a red and gold Reader’s Digest edition of Grimm’s Fairy Talesfor a quarter from a rummage sale. I think she was more delighted at the bargain price per page than she was about matching me to a book which would change my life. I loved the stories about families in it, the brothers and sisters forced to rely on their wits at a tender age. I felt a deep connection to it. Over and over, the children in those tales are unmothered (as I was when I was a baby), isolated (aside from my sister, I didn’t know many children my own age), singled out because they were different (the few children I knew were not interested in spending an afternoon in happy paired-solitude reading these stories, or making up ones of our own). Small wonder that the witches in the stories crept into my dreams, along with a talking black bear who warned me about danger as he fished in the same shallows where I waded when I woke up. Both appear in my dreams to this day. When I became a school librarian, I had the great good fortune to have a massive folktales collection in both the libraries where I taught. In encountering remakes of these tales, I started thinking about the artifacts in these tales contained. One of the anthology covers had cutouts of a single object that represented each story in it. A shoe for Cinderella, a spinning wheel for Sleeping Beauty and so on. I wondered what cutouts my childhood stories would have, and began writing a set of appendices which appeared in my first book, Alma Almanac. Those fragmented figures began as scraps of my real childhood home, but the more I wrote these tiny autobiographies, the more shards of these fairy tales I found appearing in what would become my next manuscript. The old tales always had bits and pieces rattling around their plots, dangerous and noisy. Tokens and leftovers, orphans and shoes and broken off triplets. I shook my childhood edition of the fairy tales as I took it down from the shelf, and each time, another type of brokenness entered Ever After the End Matter, another opportunity to find a piece that fit.

AARON MILSTEAD

Aaron T. Milstead is the author of They Don’t Check Out and was featured in Road Kill Volume III. His most recent novel, Earworm, was published in March of 2019 and that summer he will be featured in a science fiction anthology called Crash Code. He lives in the Piney Woods of East Texas with his wife and three children.

Mythology began to shape my view of the world at a very young age, in fact one of my earliest memories is of my mother reading The Hobbit to me as a bedtime story, a few pages at a time. Ironically, when I was old enough to read alone, I was enamored with the same Norse myths that so heavily influenced Tolkien. I must have read Edith Hamilton’s collected mythological tales (including Greek and Roman stories along with the aforementioned Norse ones) a hundred times. I can still vividly remember the wonder of imagining a baby Hercules as he intercepts two large serpents sent by Hera to kill him in the crib and how he casually squeezes them both to pulp as he joyfully giggles. Growing up in the Bible Belt I was also heavily influenced by Christian narratives that were presented as absolute truth next to these similar tales from other cultures that were presented as pure fiction. This contradiction still informs much of my thoughts about contemporary culture and frequently manifests in my own writing. Ironically, I learned, much later in life, that Tolkien’s writing was just as influenced by the Bible and his Catholic faith as it was by Norse mythology. At a very young age (seven or eight) I experienced a cognitive dissonance as I read about Isaac and Abraham and had to conceptualize a god that would ask a loyal servant to sacrifice his only child as a demonstration of faith. This narrative precipitated an existential crisis. Trauma. As has often been said, “writing is therapy”, and this narrative has been the crux of much of my writing. Luckily, around this same time I was exposed to a new form of mythology when my parents bought me a stack of comic books to pacify me during a trip to Colorado. The transition was natural and there were several familiar faces: Thor, Odin, Hercules, Zeus, Amazons and countless others. Even the heroes with different names were variations of archetypes I had already grown to adore. I would later understand this dynamic through the writings of Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung. What amplified my love for these myths was that these heroes were contemporary and somewhat relatable. It was when I was thirteen and read Alan Moore’s magnum opus The Watchmen that I realized mythology could be completely realistic. He dealt with topics that comic books had previously avoided such as racism, mental disabilities, and sexual assault. He presented the notion that heroes could be just like real people: endlessly flawed and filled with human frailties. That was the moment I realized it was no longer enough for me to just scribble the occasional story in a notebook and never to be seen again; I aspired to one day be a real writer. My most recent novel, Earworm, combines two other types of mythology that influenced me as I matured: Southern Grotesque/Gothic and Lovecraftian Horror. As different as those influences may seem, there are common threads. Transgressive or irrational thoughts. Racism. Dark humor. Perhaps most of all is the general sense of alienation; an understanding that the world is not as pure as it may seem on the surface and that beneath a thin veneer of optimism is always horror. Flannery O’Connor once said that, “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.” This is a concept that I explore as my protagonist, Ripley McCain, faces his own mortality and the loss of his only relationships. H.P. Lovecraft once said that, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” This is another concept that I explore as Ripley must determine if his fatal brain disease has caused a schizophrenic break or if the voices in his head are coming from a symbiotic entity that crawled inside his ear and nestled in next to his amygdala. Much like the authors that have inspired me I continue to recontextualize the myths that have shaped my understanding of the world.

JEANNINE HALL GAILEY

Jeannine Hall Gailey served as the second Poet Laureate of Redmond, Washington. She’s the author of five books of poetry: Becoming the Villainess, She Returns to the Floating World, Unexplained Fevers, The Robot Scientist’s Daughter, and Field Guide to the End of the World, which won the Moon City Press Book Prize and the SFPA’s Elgin Award. Her work has been featured on NPR’s The Writer’s Almanac, Verse Daily, and in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror. Her poems have appeared in The American Poetry Review, Notre Dame Review and Prairie Schooner. Her web site is www.webbish6.com.

I think there are a couple of myths and fairy tales that I’ve come back to again and again. The Snow Queen is a favorite character in her various costumes and appearances (a version of which you’ve been kind enough to publish), the legend of Philomel, the Fox-Wife myth from Japanese mythology, and the Melusine myth, which I reference rather non-explicitly in every book. The idea of a woman being a monster or a villainess, the idea of transformation both internal and external – themes I return to over and over. I’ve also noticed lately a lot of poems about solar weather, eclipses, moons, which means I may be becoming a witch myself!

GWENDOLYN KISTE

Gwendolyn Kiste is the author of the Bram Stoker Award-nominated collection, And Her Smile Will Untether the Universe, the dark fantasy novella, Pretty Marys All in a Row, and her debut horror novel, The Rust Maidens. Her short fiction has appeared in Nightmare Magazine, Shimmer, Black Static, Daily Science Fiction, Interzone, and LampLight, among other publications. A native of Ohio, she resides on an abandoned horse farm outside of Pittsburgh with her husband, two cats, and not nearly enough ghosts. You can find her online at gwendolynkiste.com.

In response to our question, Gwendolyn says:

There have been so many fairy tales and myths that have informed my work over the years, but if I had to choose just one that continues to inspire me the most, it has to be Baba Yaga.

Unlike the more ubiquitous tales such as “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Sleeping Beauty,” I didn’t come across the Baba Yaga tales until I was well into adulthood. Immediately, though, I connected with the duality of how she’s depicted in the various legends. Baba is too often reduced to a simple caricature of evil, but when you look deeper at the stories about her, she is anything but straightforward. Her character is complex and malleable, and she’s taught me perspective is everything. Historically, it’s been far too easy for audiences to reduce a powerful female character to a stereotype of danger. While Baba Yaga certainly has her more sinister side, she’s as likely to help the protagonist in some stories as she is to hinder them, making her one of the only fairy tale characters who has served both as an antagonist and a traditional “wise old woman” archetype. Exploring Baba Yaga and the stories about her has challenged and guided me in imbuing my own female characters with more nuances. No one is all good or all bad, and women in literature deserve better than the surface-level characterizations that they’ve so often received in the past. For me, Baba Yaga has become a perfect template and inspiration for how to move forward in telling better stories for women.

And besides, who wouldn’t want to ride around in that mortar and pestle of hers?

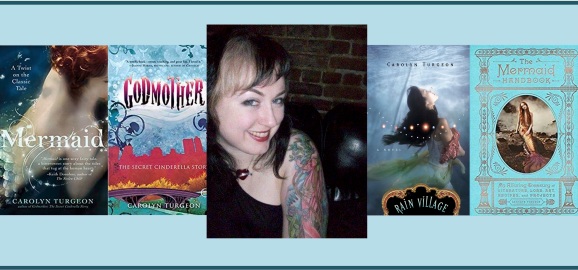

CAROLYN TURGEON

Our first respondent is Carolyn Turgeon, who is the author of five novels—Rain Village, Godmother: The Secret Cinderella Story, Mermaid, The Fairest of Them All, and the middle-grade The Next Full Moon, most of them based on old-time fairy tales—and, more recently, The Faerie Handbook and The Mermaid Handbook. She’s also the editor-in-chief and co-owner of Faerie Magazine, a quarterly print publication about which the NY Times said, “It’s as though Martha Stewart Living and Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene had a magazine baby.” Currently she’s working on a third handbook and a new novel. She lives in Baltimore. Read more at carolynturgeon.com and at faeriemag.com.

In response to our question, Carolyn says:

I don’t know that I can point to one text. I read so many myths and fairy tales as a child that I’m sure they’ve all combined into one giant blueprint that has shaped most of what I’ve done and do as a writer. The older I get, the more I realize how fundamental those first texts were, actually! Probably one of the earliest for me was Bullfinch’s Mythology, which I believe I read in an elementary school class and became obsessed with and am probably still obsessed with, at some level. I started reading as much as I could about those myths. I loved those glamorous gods and goddesses, those dazzling hybrids and transformations. I loved the moment when Achilles kills the ferocious soldier during the Trojan war, then lifts the soldier’s helmet to find the queen of the Amazons, Penthesilea. Her long hair tumbles out, and he—shocked and devastated—falls madly in love with her in the same moment he realizes he’s killed her. It’s so dramatic and gorgeous and tragic!

I loved, too, the idea that a god could place a hero in the sky as a constellation, that so many of these larger-than-life characters were now literally stars in heaven, making designs in the sky. Here’s the story of one of the more famous constellations: “… [Orion] dwelt as a hunter with Diana, with whom he was a favourite, and it is even said she was about to marry him. Her brother [Apollo] was highly displeased and chide her, but to no purpose. One day, observing Orion wading through the ocean with his head just above the water, Apollo pointed it out to his sister and maintained that she could not hit that black thing on the sea. The archer-goddess discharged a shaft with fatal aim. The waves rolled the body of Orion to the land, and bewailing her fatal error with many tears, Diana placed him among the stars.”

Just writing this now makes me realize that this moment from my first novel, Rain Village, came directly from those old myths, when my young protagonist Tessa meets the sexy ex-circus star librarian Mary Finn for the first time, a woman who’s appeared in her tiny farm town like some kind of mythical goddess and changes her life. When they first meet, Mary lifts Tessa’s hand and explains that the half-moons on her fingernails were once part of a star, and it’s the first time Tessa feels at all special or noticed in her life. “Every part of your body—the moon on your pinky nail, the blue rim in the center of your eye—was once part of a star,” Mary says. In response, Tessa feels “all lit-up and almost glowing imagining my body spread across the night sky like an explosion, sparkling down to the half-moons on my fingernails.”

Of all those wonderful myths maybe the one I loved the most, or at least the one that’s stuck with me most strongly, was the story of Apollo and Daphne. I reference it in at least a few of my books, just quick little flashes, and I actually have a tattoo up my left arm of Daphne transforming into a laurel tree. I guess all these stories involve some kind of intense tragic beauty, rooted in violence, and the story of Daphne is no exception. You might remember that Daphne is daughter of the river god Peneus, a nymph who wanted nothing to do with men, only to “range the woods” and remain unmarried “like Diana.” Apollo, who’s madly in love with her, chases Daphne through the forest. As he gains on her and reaches out to grab her, she calls out to her father for help. “Help me, Peneus!” she says, “open the earth to enclose me, or change my form, which has brought me into this danger!” And then: “Scarcely had she spoken, when a stiffness seized all her limbs; her bosom began to be enclosed in a tender bark; her hair became leaves; her arms became branches; her foot stuck fast in the ground, as a root; her face became a tree-top, retaining nothing of its former self but its beauty …”

To me, the image of this beautiful, wild maiden transforming slowly into a leaf-covered tree is so lush and rich and jam-packed. That such beauty (and freedom, possibly, in her going completely wild) would stem from a moment of such violence—that she had a way out, that she could become something else, something beautiful and wild, instead of the alternative, which was to be raped. Probably as a young girl about to enter puberty, with a body that was already changing and not by my own choice, this appealed to me: the idea of a wild, untouched girl transforming into a tree and in this way staying wild forever, a daughter of Diana. Of course, Apollo then takes leaves from the tree/Daphne to make himself a crown of laurel leaves, and this becomes the symbol for all poetry, right? Which is weird and disturbing, the idea that poetry is sort of born from that kind of violence and violation (and beauty).

As a college student and graduate student in Italian literature later in my life, I studied the poetry of Petrarch, which is full of references to Daphne and the laurel tree (which comes to stand in for his own love, Laura, who dies as a young woman), and I was fascinated by that same weirdness. And I suppose it’s possible to look at Daphne as a solely tragic figure, trapped forever in this rigid form, the leaves of which provide the content of so much human poetry. But to me she’s a sort of feminist symbol, in her wildness and her beauty and in the choice that she makes. I know there are moments in my life—and in many women’s lives—where that sort of choice would have been welcome.

In my own writing, I think I circle back and back to these sorts of moments involving transformation, and violence, and magic, and beauty, and that same strand of wild feminism, like when the little mermaid takes a potion to split her tail into legs or when the fairy godmother spreads her massive, painful white-feathered wings, or when Rapunzel (who becomes Snow White’s stepmother in my book The Fairest of Them All) eats the bloody heart.

You must be logged in to post a comment.