My sister is levity personified, a floating angel cake of a person tethered to the walking world by bright ribbons. The Light Princess, they call her. They have done so ever since our father, the kindly King, slighted his sister once upon a time. The King’s eyes, blinded by the light of a healthy infant after so many years of longing, skipped over the old witch’s name when writing the guest list for the christening.

Aunt Makemnoit interpreted the slight as a different kind of invitation. She arrived at the party in her finest gown and embraced her brother, then cursed his bouncing baby to a life spent permanently aloft.

When the curse took hold, gravity abandoned my sister’s form. It returned only when love taught her what pain was, and her tears weighted her to the ground, for a time. But as I lay here now, pinned to stone an eternity away from her buoyant presence, I think that her spirit was weightless from birth.

Reality is heavy. My sister prefers to float. After the curse, her only weighted place was the lake next to our castle, where she met her prince and swam with him. Our aunt, the witch, discovered the loophole in her spell and began to drain the kingdom of water. The prince volunteered to plug the leak in the lake with his person, and nearly perished for the pleasure of making my sister cry over his loss. The lake refilled with the power of their love. Our aunt drowned in the overflowing waters.

Our kingdom thought the curse was broken, and my sister learned to walk. But learning to walk meant learning to fall, and learning to be bruised, and learning to feel gravity as an embrace that can’t be escaped. She longed to escape it, and given any chance, she laughed herself back into the sky.

My sister was grown. The Queen was thought to be long past childbearing. But her Majesty took to her bed with a heaviness that pressed her into the quilts, her ribs locked around a burden that she thought might crush her spine. My sister came to her rooms and cried and stayed earthbound by her side, and I finally emerged into the world as my mother left it. It took three stout nurses to bear me to my bassinet. The white wicker collapsed beneath me.

That night, and every night I spent in that kingdom, I slept on the stone floor.

The first eyes I ever saw were my sister’s, wet-glazed and gleaming with emotion I could not then recognize, but know now to be rage. An empty emotion, equally untethered to the ground as joy. Our father and the kingdom expected my mother’s loss to bring my sister back to earth to take up the mantle of her rule. But she would not alight.

She bore herself back aloft despite her grief. The kingdom lauded her ascent as an act of will, but I will call it what it was: cowardice. Deliberate ignorance. She closed her ears and eyes to the world as it existed. Only her mouth stayed open. And only to laugh.

And still, I longed for her. Lacking a mother, too weighty to be held or embraced or even to lift my own limbs, I craved the light of her presence. She would float into my field of vision and sing to me, and later, she had the kingdom’s engineers craft a platform that would hold books before my eyes. The cook’s son would turn the pages, and those pages held the greatest gifts my sister gave to me. I could not dwell where she dwelt. I could not imagine lightness. But I could learn, and dwell in knowledge, and feel less alone.

If I had read the words and kept them inside that chamber with me, perhaps I could have stayed.

But I loved her too much.

She would come each day and see me, and I would tell her what I had read. Poetry, fairy tales, myths and fables. History, philosophy. Astronomy. I was insatiable, starving for words, begging for news of the world outside. But with each new page, each new fact, I became heavier. I asked my sister, “Do you know of these factories that blot out the sky?” And she would laugh and tell me she flew nearer the forests, where the air was clearer. “But I read that the forests are shrinking,” I said, and she told me that the forests that belonged to us would never shrink, and she was not much worried about trees that were not ours.

The cook’s son would tell me of the heat outside. My rooms were dim and made of cool stone, but outside was brightness and a lake that ebbed despite the witch’s death. Fiery wind. Crops that emerged green from the soil before being blasted into husks. Factories belching smoke to manufacture baubles and merchandise. Microbes blooming in warming bodies.

My sister would bring me gold and jewels and commemorative plastic water bottles from the Queen’s Memorial Races, and I would move my eyes to and fro in the head I could not shake. Stop, I would say, something is wrong. And she would laugh and float away to another speech, another factory’s opening, another interview in which she sang the praises of our kingdom’s prosperity.

“Light Princess Welcomes Historic Low Unemployment Rate of 3%,” the headline would read. The cook’s boy would shake his head and say the figure counted the children in the mines, too. “I’d be there myself if not for you.” He smiled as he held my hand.

He took ill and did not return.

The King, our father, brought prince after prince to my chamber. “Love broke your sister’s curse,” he said, and I rolled my eyes toward the back wall and down toward my feet, where the latest suitor stood, and said no. Again and again I refused, and again and again my father would return with princes garbed in clothes from beyond the edges of our kingdom, from far-off lands that I would never see, because love does not break curses. Love compounds them. Love is heavier than any curse could ever be. And I remembered the coarse hands of the cook’s son and felt wet tears collect at the back of my skull.

All I could do was speak, and tell anyone who visited me what I knew: the world outside my chamber was careening toward disaster, and there was very little time.

And so I became what all girls trapped in stone chambers become. I was an oracle. My physical senses were cut off from the kingdom, so the kingdom reasoned that my perception, my gift for prophecy, must be heightened. My chamber became a shrine. A flood of anxious pilgrims came to me, and I told the truth to them all.

My sister, the one I longed to hear me most, floated through the sun-baked air and avoided me, as she avoided all things that could pull her to the ground. Her levity depended on ridding the kingdom of heavy things. She would have preferred, I think, to let someone else remove me. But the only force strong enough to bear me away was her own lightness.

When she came to me the last time, she sang that she was keeping me safe from the world. We both knew it was a lie. But to me, held and carried for the first time, those moments of flight in her arms were worth forgetting the truth.

She had built me a comfortable home. The stone was soft. The kingdom’s finest magicians and engineers had contrived spells to bathe me, to feed me, to turn the pages of my books. I could dwell with knowledge forever. But she would be gone.

I am ashamed to admit that when she let me go, I clung to her. I willed every force of nature—gravity, grief, love—to bring her aground. To not leave me alone.

She struggled to break free. I begged her to listen. The world is melting, I cried. The world is on fire. It will all end badly.

My tears carried no weight.

I watched my sister fly away and return to the subjects who welcomed her laughing lies, in the kingdom that has banished reality. When I close my eyes, I still see her silken tethers swirling in the wind. The Light Princess rules still from the ends of her ribbons and ropes.

But the old witch, our aunt, had worked powerful magic. I have read enough astronomy to know what I am. Each day, with every turning page, my gravity increases. My exile compounds my longing. My grief exerts a force that will grow to eat the world. A loss of gravity must, at some point, be balanced by a surplus.

Even light cannot escape, in the end.

Audrey Burges

Audrey Burges writes in Richmond, Virginia, and her satire and essays have appeared in a variety of outlets, including McSweeney’s, Medium’s Human Parts, Empty Mirror, Slackjaw, and The Belladonna Comedy.

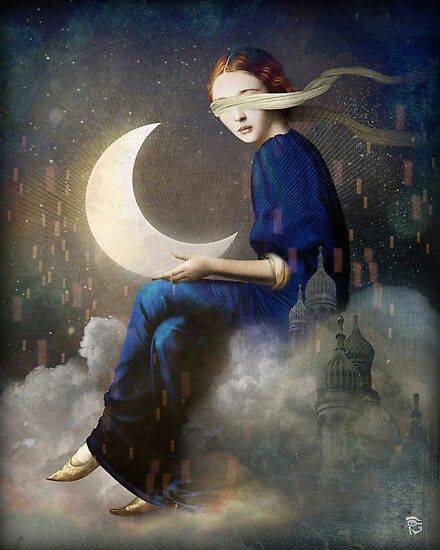

Artwork: Christian Schloe, Kingdom of Clouds

Website: https://www.facebook.com/ChristianSchloeDigitalArt